Ukraine is not going to be clan-oligarchic any more. What changes will be in the interest group pattern after the war

Mind Intelligence analyses why the oligarchial model is gradually losing its leading part

The war fundamentally changes both political and economic models of the Ukrainian state organisation as well as relations among them. The whole class of oligarchs passes into history, which for almost 30 years determined not only the dynamics and quality of Ukraine’s economic growth, but also the internal and foreigh policy of the state, and the development of the whole society to some extent.

When the war is over, Ukraine will find itself in a new reality with new special interest groups. They will have completely different priorities, employ other instruments of pressure on the authorities and mechanisms of lobbying their own interests. The new system will not be better or worse. It will be just different, and we have to be prepared for this.

As part of the Mind Intelligence project we present our opinion and analysis of changes in relations between the business and the government that are already underway and will go further. The author expects to start with this piece a discussion about the Ukrainian track of economic growth. Our editorial team, in its turn, is ready to publish alternative opinions or additions to this material.

On the Ukrainian track of economic growth and its unique character

Almost the entire 30-years’ history of Ukrainian independence has been inseparably connected to the clan-oligarchic model of state organisation. This means not just the economy of the country. Specific and unique character of Ukraine was in that the oligarchic groups that had developed into the financial industrial conglomerates (FICs) became not just economic units, but the key special interest groups in the state, defining its lines of development in numerous spheres.

FICs’ interests influenced the formation of the political system in the state, determined the country’s foreign integration vector and its role in the world economy. Moreover, FICs exerted a great deal of influence on the media sphere of the nation, its culture and sports development. In the end, neither Ukrainians, nor the world have known Ukraine without powerful FICs. This has always caused damage to the country's image and shaped critical perception of their own country in the eyes of Ukrainians themselves.

There is no doubt that the absolute majority of citizens consider and have a negative perception of the role of oligarchial clans in national history. The latter are traditionally blamed for causing critical problems in the country.

But does it correspond to the truth and was there any alternative?

The realities are much more complicated. After the command-and-control model of economics had deteriorated, Ukraine went on a somewhat different track than the European post-socialist countries. The latter opened themselves for western investors and regional organisations at once. They were rather quick to implement the best western practices and to switch to a free-market economy.

In Ukraine, the process of forming a new economic model was going on by its own strength. Economic assets were rapidly taken under control by those who came from various backgrounds – Communist party figures, the “red director” and the academia classes, and even criminal circles. A concrete individual’s personal traits, his inner energy and dexterity, not social descent, made then the greatest difference.

Owing to favourable configuration of various factors and specific individual skills, representatives of these environments turned out to be the owners (technical or actual) of industrial enterprises which they privatised later for symbolic price.

Such enterprises often got a wide list of fiscal preferences, subsidies, and a high level protection within sectoral development programmes, thus becoming a source of fast capital accumulation. Financial resources were used for the further expansion. At the first stage they were directed mostly on vertical and horizontal integration of business.

The need to support financially the operations of such aggregations furthered purchasing at first financial institutions, banks and insurance companies by most clans and even investment companies, by some oligarchs.

The financial structure shaped this way performed not only standard financial support tasks of the whole conglomerate, but was actively used to optimise taxation and for pulling capital abroad as well. (Frankly speaking, it has to be noted that a great deal of those funds returned to Ukraine in the shape of foreign investments). At this very stage, chaotic structures began to transform into organised financial industrial conglomerates.

In the 2000s, Ukrainian clans, being in dynamic growth, reached a new stage in their development – they started to invest in high-tech sectors of the economy, real estate and to purchase assets abroad. This contributed to sectoral and geographical diversification of FICs. There was a time when they were influential actors in Central and even Western Europe.

While developing their businesses, oligarchic clans invested in sport, social, and cultural projects, which was also quite important for the making up of Ukraine as a state.

As an effect of years of crystallisation of the clan-oligarchial model, a rather big number of FICs formed in Ukraine, most of which had very similar organisational structures.

These were the essential elements of absolutely most oligarchial clans:

- industrial assets (often vertically integrated corporation);

- financial framework (a bank, an insurance company, an investment company);

- real estate in Ukraine and abroad, including commercial and dwelling one;

- informational structure (personal mass media, think tanks, a pool of loyal experts and journalists);

- political division (own parties and politicians, political allies, bribed bureaucrats etc);

- a number of sport and cultural projects (nearly always a football club).

Read more: Mind Intelligence: how the war transforms the agro-industrial complex

During 2005–2010, the clan-oligarchic model reached its prime. This stage in the history of Ukraine may be called the “oligarchic democracy.” It was characterised by some degree of pluralism of special interest groups.

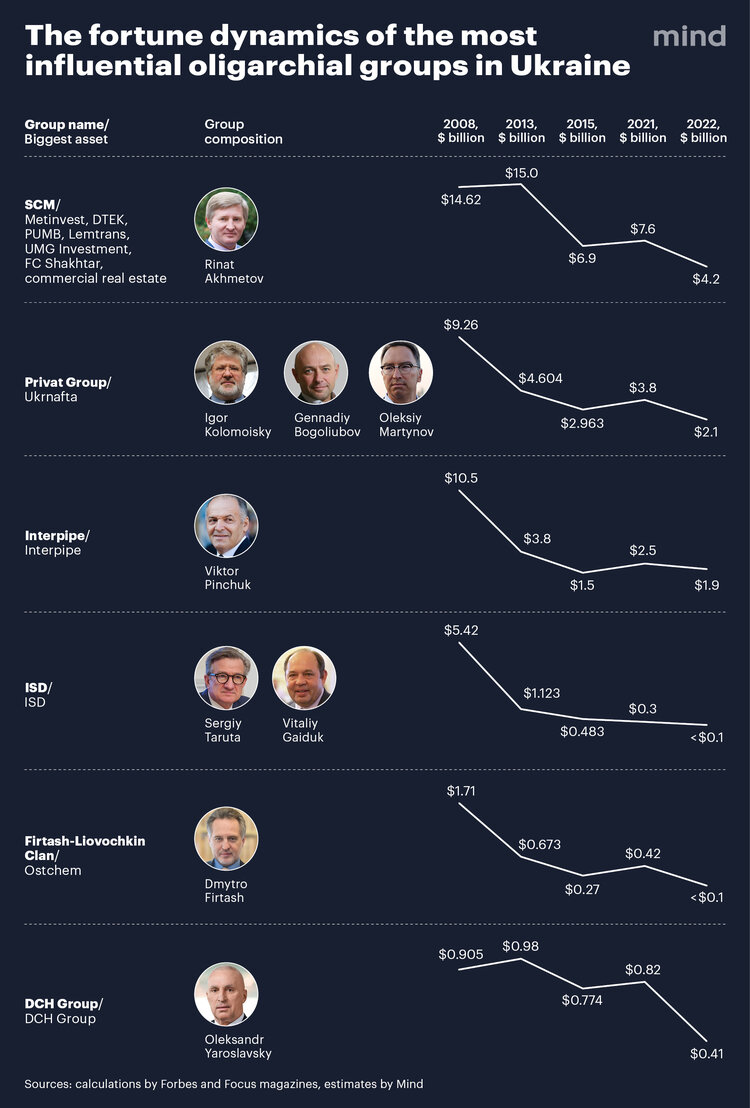

Then there were about 20 FICs in the country, namely: SCM (Rinat Akhmetov), Privat Group (Igor Kolomoisky, Gennadiy Bogoliubov and their partners), Interpipe (Viktor Pinchuk), ISD (Segiy Taruta, V. Gaiduk), the Firtash/Liovochkin Clan, Yaroslavsky Conglomerate, the Poroshenko Clan, Kostiantyn Zhevago Conglomerate, Smart Group (Vadym Novinsky), Egergostandart Group (Kostiantyn Grygoryshyn), Ukravto (Tariel Vasadze), Nibulon (the Vadatyrsky family) as well as several other smaller groups, including ISTIL Group (Muhammad Zahoor), Energo Concern (V. Nusenkis, G. Vasilyev), TAC Group (S. Tigipko), Ilyich Iron & Steel Works Group (V. Boiko), Boguslayev Group, conglomerates of O. Bakhmatiuk, the Surkis brothers and the Kliuyevs brothers.

The FICs mentioned were at different stages of development and naturally had not the same scope of influence on politics and the economy. At the same time none of the listed groups had absolute and monopoly influence in the country.

This created a system of checks and balances of a sort and prevented the country from falling into totalitarianism where the rf and belarus had already ended up.

Common interests forced oligarchic clans to agree and seek compromises (this immediately was reflected at the political level as political coalitions). Superfluous appetites of competitors and influence abuse forced them, instead, to unite to cope with the threat of power monopolisation.

Almost each of those clans owned a mass media and political projects, which provided a pluralism of opinions and positions in the national media and political spheres. It was no accident that in 2005–2010 there was a true parliamentary and presidential republic (again, oligarchic) functioning in Ukraine.

Viktor Yanukovych celebrating the Power Engineer Day on 20 December 2013

The “oligarchic democracy” model began to fall apart only when a couple of actors did gain asymmetric influence within the system and went too far in their expansion. Besides, the exclusively aggressive Yanukovych Clan (known as “the Family”) that intended to build in express pace of several years a FIC of the scale oligarchs had spent two decades building, finally broke the balance.

The very factor of grievance that some certain FICs changed the system in their favour using political instruments at the cost of interests of others, became among the most essential ones, speeding up the outbreak of the Euromaidan protests.

The 2014–2015 war events, financial and exchange crises and the EU association ultimately undermined the economic basis of the oligarch class, reducing their influence on the situation in the country as well.

But for some time the clan-oligarchial model operated mechanically because a representative of this class raised to the presidency. He (as well as his partners) did not have any intentions to break the system, instead to just change in their favour by political instruments. Due to this, in 2014–2019 one could witness a change in position and sphere of influence of individual FICs, but not the fundamental reshaping of the organisational model of the state.

Because of these trends the number of influential clans shortened from two dozens to four. But for all that two among them in fact monopolised the influence on the government. Such a model could not be called pluralistic – rather monopolistic.

It retained the worst traits of the clan-oligarchial model, thus it was predictable that a new protest would burst in the society. The difference from 2013 was that the protest occurred peacefully via presidential elections.

First, it undermined the financial strength of FICs which now have significantly less abilities to fund and support political projects. FICs nowadays have neither large quantities of free (floating) cash to finance politicians, nor the developed information framework by which they “produced” their own politicians and got the loyalty of the existing ones.

Second, the war has already strengthened government institutions. More important processes are going to take place after the war, namely the great consolidation of the political elites’ influence. No doubt, a great deal of militarymen and people with background in administering the state at war will come to power. Such politicians and public servants will not be the obedient executors of the oligarchic will a priori.

Third, most oligarchs decided to leave the country. This will have fatal effects both for their political position in the country and for their property in Ukraine. New special interest groups that have stayed in Ukraine will undoubtedly take advantage of the opportunity to start the redistribution of assets and spheres of influence.

As of now the Firtash/Liovochkin Clan, Yaroslavsky Conglomerate, Kostiantyn Zhevago and Oleg Bakhmatiuk’s conglomerates suffer energetic attacks.

This process is not going to cause social dissatisfaction; it is likely to find even support in the society.

On the main drawbacks of the clan-oligarchial model

One of the key results of 2022 in Ukraine will be the dismantling of the clan -oligarchial economic model that was inseparably linked to the formation and development of Ukraine itself after it has restored its independence.

Ukrainian society is prone to seeing chiefly positive effects of this process as it has a deeply entrenched belief that this model is marked by big dangerous drawbacks that constrain the development of the state. Such do exist, of course.

First is the total corruptibility of the political realm and government bodies. FICs have trained domestic politicians and bureaucrats to have bribes, kickbacks and other informal payments. It is no secret that many Ukrainian politicians and public servants had their essential career goal not in serving the state (or at least in realising their ambitions), but in getting a job at FICs.

Russian oligarch Vadim Novinsky and the Prime Minister of Ukraine Yuliya Tymoshenko at a conference with managers of mining and smelting complex and chemical industry in Kyiv on 23 October 2008

Second, FICs contributed to monopolising the entire sectors of the economy – energy, fuel industry, mining and metals sector, fertiliser production etc. But for all that, the worst is that they do not have any sense of proportion. Most FICs would like to have absolute monopoly in the desired field of the economy.

Almost each time after this task had been achieved, the corresponding sector and markets faced a complex of problems, first and foremost, an unjustified rise in prices and deteriorating quality of goods and services.

Read more: Mind Intelligence: how the war will change the fuel and energy complex

Third, powerful FICs are used to exploiting state resources in their own favour. They consider other segments of the economy (infrastructure in the first place) as their own supplements. The most influential oligarchial clans, exerting their influence on the bodies of state administration, exploited national assets for a trifle for quite a long time: deposits, water, electricity, railway, sea ports, some resources produced by state-run corporations etc.

Fourth, there turned out to be too many disreputable persons among Ukrainian FICs (concrete oligarchs, to say more correctly in this case) who did not feel any responsibility neither before their own enterprises, nor their state. They focused their activities mostly on extorting financial resources from the country and pulling them abroad to be invested in luxuries.

Ones used their banks to collect money from the population, which were later stolen, others avoided taxation for their own enrichment, third ones parasitized public contracts, the fourth abused their monopoly status. There were also the ones who exploited all mentioned schemes.

Fifth, a part of FICs turned out to be the rf agents. Powerful oligarchy clans have been always used by the kremlin to realise its own geopolitical plans in Ukraine. Rather popular was the scheme of giving loans to national FICs by russian banks (often the state-run ones).

We may assume that later some part of these funds was used for internal payments with Ukrainian politicians and bureaucrats for lobbying the rf interests. Such a mechanism is quite comfortable as it allows avoiding suspicious cross-border transactions.

Some FICs working for the rf went over to moscow back in 2013–2014. But Ukraine succeded in stabilising the situation and traitors had to flee the country for russia.

A great deal of FICs working for moscow did it more delicate, so they operated in Ukraine without any problems. Their ties to kremlin became clear only when the full-scale war broke out. But the most dangerous thing is that a part of domestic FICs being the rf agents continue to operate in Ukraine pretending to be supporting the Ukraine Army.

Six, Ukrainian FIC bear the top responsibility for the fact that the Ukrainian economy remained closed to western investors and Ukraine itself moved towards its dependence from the rf. This is indeed a fundamental problem. It became apparent in many spheres. In the realm of the economy the state lost enormous potential revenues because the access to privatisation was blocked for western corporations, mid-size business was cut off the civilised business practices and available funding, and citizens, from cheap and quality import.

At the level of politics this led to intensified integration of Ukraine and the rf, which caused distancing from the Western world. The logic of the national FICs was understandable enough. It was rather hard for them to compete in European markets, instead they felt themselves quite confident in markets of the CIS.

Absolutely natural, that under those circumstances their advantage was in synchronising the economic space with russian integration projects to reduce trade barriers for entering markets as much as possible. FICs were the key special interest groups being an obstacle in the way of European integration of Ukraine.

The mentioned demerits are the inherent components of the clan-oligarchial model of the state. If the collapse of this model meant the automatic elimination of all these problems, we could forecast the Ukrainian economy and the state in general would make a giant progressive step towards their development as a result of this process.

On the merits of the clan-oligarchial model

It should be remembered that positive elements of the clan and oligarchy model will drop out together with negative ones. No matter how unpopular this argument may be, the national FICs made a significant positive contribution to the development of the country.

First, they secured the industrial potential of Ukraine. After the USSR had fallen apart, key industrial enterprises were divided. Ones fell under control of the domestic FICs, others passed to foreign investors (mainly, the russian), some remained in the possession of the government. Nowadays, we can see quite clearly who appears to be the most efficient owner.

Enterprises purchased by russian investors (oil refineries, non-ferrous metallurgy enterprises, a number of machine-building plants) were neglected, shut down or dismantled (or reselled) before the war.

Enterprises that have remained in state ownership (first and foremost, in avia and space industries and the defence-industrial complex) gradually deteriorated and their status is now dreadful. Only short-term factors gave them an incentive for development.

There were also rather high hopes on the foreign (western in the first place) capital in Ukraine, but they have not always been reasonable. The case of Warsaw pact countries shows that West European capital rather often bought high-capacity industrial enterprises for the purpose of dismantling or reshaping them. As the russian one did in Ukraine.

If we look at modern economies of the post-socialist countries in Central Europe, we may notice them losing a substantial portion of their industrial potential.

The same scenario would await Ukraine either. International corporations would shut down many crucial industrial enterprises considered to have no prospects. Thanks to the fact that the control over Ukrainian industry had passed to domestic FICs, the country managed to save its industrial potential.

The argument that national oligarchs have plundered enterprises they inherited from the USSR is absolutely populistic. The truth is chiefly that although they had got these enterprises for cheap, they made a positive contribution – set up production and started to invest.

Many examples can be found for sure, but they did not break the general trend. Enterprises owned by domestic FICs looked quite good before the war.

Second, domestic FICs were the effective special interest groups who lobbied interests of the national producer. Sometimes too aggressively, sometimes failing to understand certain limits, but the government would pay much attention to developing national production and domestic business under their pressure.

European liberal alternative (in 1990s)

Western institutions have always demanded maximal liberalisation of the national economy and opening it as the critical prerequisite for political and economic integration to European structures. But the absolute levelling of business conditions was indeed a quite unfair practice and had nothing in common with creating equal terms for everyone.

The matter is that European corporations were at a much higher technology level, they had access to cheaper funding in their countries and much bigger experience of operation within a free-market economy. The demanded common market with equal rules gave a priori more favourable starting conditions to them, not to the national business.

Post-socialist countries that implicitly took Western terms on absolute liberalisation of their economies, in fact lost their industrial potential and work as component producers for the corporations from developed countries. A rather dubious economic success.

In the last years domestic FICs took a quite constructive position on this matter. They rejected the aggressive protectionist policy but justly demanded that the government introduce supporting instruments that would assist the domestic business in adapting to European standards.

Third, the national FICs provided a great deal of currency flows to Ukraine and budget incomes at all levels. Besides, they created many jobs. Owing to this, they played an important positive role in stabilising the situation during periods of economic turbulence.

When there are first signs of worsening of the economic situation, they begin to radically optimise taxation and largely fire their employees, encouraging the further worsening of the situation. In Ukraine, FICs have always tried to avoid any sudden movements in worsening situations (often pressed by the state), owing to which they served to some extent as stabilisers of the domestic economy.

Fourth, the FICs gave positive incentives for the development of other sectors of the economy and spheres of the state. One should remember that multinational companies are not likely to invest significant funds in the country and region’s economies. Most Ukrainian oligarchs in spite of their demerits have spent much on the development of local communities, namely on infrastructure modernisation, culture and sports development etc.

This was driven partly by pragmatic calculations, namely the intention to improve their image. But also such investments in part were, probably, the result of the evolution of the very oligarchs who matured from aggressive capital accumulation to some sort of accountability for the status of the state and regions’ development, where they have spent a long period of their lives.

Lately it was quite popular among national FICs to invest in innovations, start-ups and even the development of national education. Multinational corporations did not usually spend costs on such projects in Ukraine.

Fifth, many national FICs contribute invaluably to the support of the government in the war time. Numerous experts have a rather sceptical and unjustified approach to the idea of “national capital”, but this is a rather important factor in practice. This may be especially seen in the conditions of war. Most national FICs redirected to the support of the state, and powerful international corporations, instead, just ceased their operations in Ukraine, confining themselves to making donations to the Armed Forces of Ukraine to the best.

On the consequences of the clan-oligarchial model collapse

Unfortunately, the reverse side of this process is forgotten, namely the perils brought by the process of the clan-oligarchial model collapse. They are rather considerable and ignoring them may have very negative effects both on the state and on the concrete political and economic actos.

First of all, the very collapse of any model of economy no matter whether or not it was acceptable for someone, is a great shock for the society and the state. Each model is a complex aggregate of interrelated elements and ties among them, which are integrated in a unified mechanism, securing the operation of the economic system.

For some reason, there was consolidated a belief in the Ukrainian society that “bad elements” (the oligarch class in this case) can be just deleted from the “bad model” and it will automatically turn into a high-developed socialism model of Nordic type (the most beloved economic model by the Ukrainians).

President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko and ex-Head of the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast State Administration Igor Kolomoisky at the meeting with the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast leadership, introducing the new Head of the Dnipropetrovsk OSA Valentyn Reznichenko, 26 March 2015

In fact, the collapse of the clan-oligarchial model does not mean that a more progressive model would emerge in its place. The latter would not emerge spontaneously. A huge amount of work has to be done in order to form a more progressive and efficient economic mode.

And this work is not being done, because the state faces more relevant tasks. Now almost nobody knows what will replace the clan-oligarchial model of economy. The worst is that no one tries to think over this.

Ukrainian society has a radically negative attitude towards this economic model, but it does not really have any experience of functioning within any other model.

After the clan-oligarch model finally collapsed, the society will find itself in a state close to the situation of early 1990s when the command-and-control economic system was destroyed, but citizens were not ready to accommodate rapidly to new realities. The accommodation period for the new model took nearly 10 years. This was, in fact, a lost decade. Such a threat is now relevant again.

So being dominant until recently, FICs were not as destructive as they were usually thought to be. Weakening of their influence in the country will have complicatedly predictable effects.

Some negative phenomena will fall away, related to the FIC dominance, but also some quite important mechanisms will be destroyed that secured the economic and social development of the state in the last years.

The age of new interests and new specific interest groups

Decreasing role of FICs in the economy and the state will be accompanied by simultaneous rise of the new specific interest groups’ role. It cannot be outlined yet who will seize dominant positions in the country, as it depends on various factors.

At the same time, if the basic scenario is the end of the war with acceptable results for Ukraine, we can predict that the following specific interest groups will be set forth.

Western partners

Until lately, the one who generated high revenues and foreign currencies flow had the strongest positions in the country. These were with rare exceptions the national FICs who output and exported their produce abroad. The stable cash flow allowed them to influence political processes. This situation can change after the war.

The operating principle of the system will remain the same – he who controls the flow of funds, influences the policy and policy-making to the largest extent, but the key financial flows will come to Ukraine from abroad.

Financial injections in Ukraine at first will be provided by western and international institutions and organisations. Even the FICs themselves will be forced to ask them for financial aid to restart their economic activity, so they will agree on their leading role in the political and economic life of the country.

Ukraine will have several sources of financial injections. These are international financial institutions and organisations (IMF, the World Bank above all), including the European ones (EBRD), certain countries (the USA, the UK, Germany. Poland) etc.

Moreover, some mechanism of reparations will certainly be developed later, that also must provide enormous financial inflow in Ukraine. All these financial incomes will be under thorough control by international and European institutions and organisations, that is why they will need an effective framework for influencing Ukrainian authorities.

The key thesis of the government which simplistically sounded like “give us money and we will spend it on our own” was accepted extremely sceptically, even somehow ironically, in the West.

Ukrainian political elites wrongly think they would outsmart western institutions and organisations as they regularly did with the IMF. Western partners, indeed, have always been aware of how various kinds of financial assistance to Ukraine are spent.

They shut their eyes to some things but do this absolutely consciously, driven by quite pragmatic and rational motives. The fundamental problem with Ukrainian bureaucrats is that they do not understand this, thinking that each time they managed to outplay and outsmart western partners.

Western partners, in general, could have let themselves ignore some abuse by the Ukrainian authorities, but this did not mean they have never noticed them. It was just the format of cooperation that did not demand any strict reaction to such abuse.

After the war ends, the situation will change dramatically. The question will be not a couple of billions of the IMF loan, but huge financial injections.

First, western partners will be interested in ensuring that the Ukrainian government does not steal the principal part of them. Almost nobody in Ukraine itself and abroad has any doubt that every Ukrainian government has a turn for this. The current political team is no exception. Their appetites will be hard to constrain without strict control.

Second, western partners undoubtedly want to influence the directions of spending funds that will come to Ukraine for the post-war restoration of the country. And they will use it in their own economic interests.

Because of this, western partners will form quite effective mechanisms of influencing the authorities and are going to be very active factors that affect policy-making in many realms. There should not be any doubt that they can effectively “cooperate” with public government bodies and political elites of the state.

We can ascertain with confidence that at least during the country's restoration period their influence on the Ukrainian government will be decisive on many issues.

The European Union

By now, Ukraine has known the EU only from one side – as the partner that has closely, including financially, supported the country. It should be clearly understood that the EU was interested in shaping a stable terrain near its astern border above all.

The EU was ready to invest rather big money to support economic and social stability in the country. Besides, it was a quite interesting and bulky market for European firms.

These priorities shaped the EU policy towards Ukraine. As a part of cooperation Brussels demanded that Kyiv should chiefly implement certain anti-corruption mechanisms (in order to guarantee the financial injections in Ukraine would not be stolen) and liberalise the access to the domestic market (to open it for European companies).

To lesser extent was the EU interested in the real internal growth of Ukraine, including its economy. This could be seen at least from the fact that the EU refused to extend to Ukraine its highly effective instruments of promoting qualitative transformations in economy it uses to intensify the development of members and candidate states.

Including Ukraine to the Framework Programme Horizon 2020 (Horizon Europe since 2020) was the exception, but to a great extent it was a symbolic step.

It has to be clearly understood that the very moment when the EU adopts the final political decision to let some country become a member of the community is the beginning of a completely new stage in the relationship between the Union and the candidate country.

It hardly looks like equal partnership, rather the “teacher–student” model. There is nothing bad with it, as each country preparing for joining the EU needs to do a huge amount of work, primarily in adapting and harmonising its legislature and other legal acts.

Harmonisation and adaptation of the law and practise is a very routine job that may take a few years. Without doing it Ukraine cannot technically join the EU, because the EU membership is not just absence of borders but primarily adopting European rules and standards in the essential spheres of social relations, from the economy to judiciary. Ukraine will have to rewrite most of its legislation, as well as implement very important amendments to the Constitution.

The EU has shown restraint in evaluating the process of Ukraine’s adaptation to its membership in the commonwealth so far. Though a critical thing should be clearly understood here. It is a big mistake to think the EU is absolutely satisfied with the progress made by Ukraine.

This in fact conveys only that the European community has not passed a final decision for themselves yet on whether to invest their time, finance and efforts in affiliation of Ukraine (in spite of all political declarations and decisions). This is absolutely clear, since the EU will wait with it until the war ends.

On the other hand, if the decision is made, the EU government bodies would be the key actors who will influence policy-making in many realms of the Ukrainian state.

Within the next few years, if they do not sabotage European integration, the Ukrainian authorities will be busy exclusively at realising tasks of the European governing agencies. All this is necessary for our country to be technically able to enter the EU common economic and customs space.

This process will generally have positive effects for the national economy, though some conflicts should be expected between national interests and the EU requirements (it is vital that they occur within the limits of positive discussion).

Importantly, the influence of the European government bodies will be predictable. If it is essential for somebody to know, in what direction Ukraine will move under the EU influence, the answers can be found in the appropriate chapter of the acquis communautaire.

In case Ukraine starts the real process of preparation for joining the EU, a separate line in cooperation with the EU will be financing programmes of “pulling up” the economic growth of the country to average EU values from the community’s assets.

European investments will be channelled primarily in modernisation of infrastructure, rural communities’ development etc. The EU will try to overcome the gap between the growth of Ukraine’s economy and the community’s even before the official affiliation of Ukraine to the Union. (Such an approach is applied to every candidate country).

Considerable finance injections will be accompanied by establishing rigid control on the side of the EU governing organs over spending these funds. This will be a completely different level of influence than the one Ukraine faced in its cooperation with the IMF.

On one hand, this will undoubtedly have a positive effect for Ukraine. Practice shows that the corruption level decreases in the candidate countries owing to such control. Moreover, an effective public finance management model is established, remaining even after the EU relaxes its control in this sphere.

On the other hand, the EU will exert a significant influence on the lines of spending funds and, what is the main thing, will try to shape circumstances that will favouritise European corporations when public contracts are distributed. In other words, the EU will allocate a lot of money for the development of infrastructure, but we should understand clearly that the most substantial and attractive investments will pass to European corporations.

In this respect, Ukrainian enterprises should not expect a golden age for them and enormous state demands would fall on them. By contrast, they need to begin to work hard to obtain at least a tiny portion of those public contracts funded by the EU.

It is also worth mentioning that due to the system of complicatedly engineered tools for funding these projects, European corporations will have better access not only to getting public contracts from the EU, but also to every project that is financed from public funds, including the budget of Ukraine.

Political clans and groups

There is a high probability that for the first time in the history of Ukraine political actors will come to leading positions in the state after the end of the war, freeing themselves from the dependence of FICs.

Numerous factors will make for it, but the main among them would be the weakness of the very FICs parallel with the great strengthening of the public authority and increasing its role in distribution of financial flows.

The key factor in strengthening institutes of public authority is the effectiveness in waging war with the rf. Ukrainian society might have discovered with some surprise that Ukraine is not a failed state in spite of all problems.

The Ukrainian state as a political institution turned out to be a rather strong organism. Not only is it able to confront military threats, but also to organise vital functions in a time of war. Though there are many rather shady personalities present in the state leadership, the level of social credibility to it as an institution has grown greatly and will undoubtedly remain at a quite high point in future.

It seems like for the first time in the history of Ukraine the state began to be viewed by the society as a value per se; so the public authority bodies’ he leading position in various realms of social relations (no matter, is it good or bad) will manifest itself for a very considerable period.

In pragmatic terms it is the very state, the certain political clans and groups more properly, that will control the key financial flows, increasing its influence and status automatically.

First, this is connected to the above-mentioned considerable amount of financial injections which will be done by international partners of Ukraine and the EU (in case a positive scenario for Ukraine develops).

Ukrainian authorities, no doubt, will be under tension by external actors, but later they will have certain space for manoeuvring in the business of distributing the received financial means.

Nowadays it is broadly clear that the prospect to control the potential billions euro or dollars that would come to Ukraine has already been agitating many political clans and parties.

Opposition forces have intensified their struggle for power and internal specific interest groups inside the ruling team without waiting for the end of the war are already fighting for the right to control the distribution of financial flows in the course of restoration of the country. One should not have any illusion in this context – future personnel rotations at the highest levels of the state administration will be done keeping the control over the future billions in mind.

This, of course, is not ethical and responsible behaviour, but it has to be known that amounts involved are so huge that domestic political elites would not be able to help to refrain from conflicts in this matter. There is a considerable risk they will be entangled into this struggle too early.

Second, the situation turned out that key sectors of the economy where significant incomes will be produced have been in the state ownership so far (these are primarily: energy, fuel industry, infrastructure, defence-industrial complex). Such strong state-run corporations as Energoatom, Naftogaz Ukrainy, Ukrenergo, Ukrzaliznytsia etc are going to be much more profitable in the near future than private FICs.

Attractiveness of the public sector and a wide range of opportunities opened by the presence in power will intensify the struggle for it and for retaining it. Powerful politico-bureaucratic clans will surely appear in Ukraine, uniting with the purpose of getting juicy government positions or state-run enterprises.

Some groupings will emerge around powerful public enterprises. By controlling its financial resources, they will be able to hold their positions in them under any political configuration.

As of now, a number of examples can be seen, how certain clans who had got attractive state enterprises under their provisional control rooted themselves so firmly, becoming able to retain their power in spite of the presence of supervisory boards with quite a strong influence of western partners who would like to see there effective manager teams.

Thus, in Ukraine, there comes an era of domination of the political clans and groups free from commercial interests of FICs and guided only by their own beliefs and interests as well as recommendations by western partners and the EU.

This in theory sounds like great progress in the country’s development, but in practice it is hard to affirm unambiguously that such a change will be exclusively useful for the state. There are very big doubts that Ukraine’s political class has matured to such a responsible mission or they will not forget about it, once they get access to enormous financial flows.

Sectoral associations

As soon as the prospect of getting European Union membership turns to the side of practical implementation, dozens of various associations and unions will mushroom in Ukraine. These would be both general entrepreneurship associations representing business interests in general and unions of narrow-sectoral business communities or individual closed clubs of influential players in important industries, for instance.

They will try to make tight connections and strategic cooperation with the government bodies.

These are normal lobbying organisations in the Western world. They articulate interests, needs and problems of business, approach the authorities with requests or suggestions on how to improve conditions for performance of business or representatives of a certain sector.

But in Ukraine such sectoral associations will be characterised by some peculiarity. It is worth remembering that they will no longer be the associations of Ukrainian business representatives, but associations of business operating in Ukraine.

Similar associations are often founded by the very western actors to lobby their own interests in the first place. They will offer attractive terms of membership for Ukrainian businesses owing to what they will include numerous national companies hiding real organisers behind them.

Generally, many may notice that such a practice has already been employed in Ukraine, especially after the EU Association Agreement was signed and the free market zone was created. It is not hard to imagine what scope will it reach, when hundreds of billions of investments in the Ukrainian economy and restoration of the country will be at issue.

“Honoured” oligarchs

The war has undermined the financial basis of oligarchial clans and their ability to exert influence on the government. No doubt, some of them will be able to infiltrate the authorities with a few agents or “persuade to cooperate” active politicians and bureaucrats in the future, but the scope of such practice is going to be limited.

For them it seems unlikely to further incorporate the whole parties (political factions at least) to the parliament or buy the whole ministries.

At the same time, for some of them the war has shaped new ways to influence the government. But this influence will be built on completely different grounds, above all, the authority some oligarchs achieved during the war. The point is that it let them reveal their essence and change the attitude in the society and the government toward them.

Most Ukrainian oligarchs discredited themselves critically. Stories of taking out watches, yacht vacations or visiting casinos in Monaco during the war devalued the influence of certain persons, perhaps, forever.

Instead, there turned out to be the ones who had entered actively in assisting the state in its war with the rf. There is no secret that the Office of the President as well as the local self-government level cooperate and interact with a number of oligarchs. In some cases this partnership was exclusively critical for guaranteeing the state defence and aid to refugees.

Owing to this, oligarchs who provide tangible assistance have greatly improved their image. Contacts between them and representatives of the establishment after the war will no longer cause such scandals and social dissatisfaction as they used to do.

The war has shown that certain oligarchs can be of great benefit to the state. Someone aided the Army to defend cities, others helped to farm communication channels with world leaders etc.

Such collaboration will also persist after the war. No doubt, some oligarchs will actively take part in the post-war reconstruction of the country. Some may even become the unofficial OP officers in charge of the recovery of certain regions.

In one way or another, certain names will retain their influence on the government, at least at the counsel and partner levels in various projects. But now there is a hope that after the war they will, nevertheless, start to think not only in terms of their own business interests, but also state ones.