"A granny brought Kevlars for the Army from the US in 62 suitcases": How civil volunteers semi-legally equip the military with everything they need

And how customs officers line their pockets on it. A story by Mind. Part 2

In January – October 2022, one of the largest charitable foundations in Ukraine, Come Back Alive, raised almost UAH 5 billion in donations. This amount was accumulated thanks to the great trust that has emerged to this organisation over the years. For all the years of its existence, it has never been involved in a scandal related to the misuse of funds. That is why, for example, in October this year, the daily revenues here ranged from 5 to 35 million UAH.

The graph shows the daily receipts to the bank accounts of the Come Back Alive Foundation in September 2022. Additionally, the foundation receives donations in cryptocurrency.

Andriy Rymaruk, the Head of the Military Department at Come Back Alive says the workload increased significantly after the start of the full-scale invasion, and therefore their staff had to be doubled. Random people were not hired – only by referral.

"Our salaries are average on the market. But the Foundation has become attractive on the labour market because of the honour of working here and our integrity," says Rymaruk, "Our accounting is crystal clear: anyone can see how the money was spent, the whole timeline. And this shapes the base for trust."

The organisation frankly says that people work here for money. Some philanthropists purposefully donate funds for the pay-roll. "People have been working 24/7 since February 24, we cannot afford to rest and go on vacation. Because the war is ongoing. So it is fair that our activists get compensation for their time – they have to live for something," they explain here.

The office of the Come Back Alive Charity Foundation partially serves as a warehouse of military equipment for the needs of the Armed Forces of Ukraine

Working 24/7, the foundation's employees show their effectiveness in numbers. Having analysed the procurement by Come Back Alive for 2022, we have not recorded any single case of overpayment per unit of goods compared to market prices at the time of purchase. On the contrary, the organisation saves millions of hryvnias on large batches of goods.

For instance, one of the foundation's largest purchases was made in the first week of the war. On March 1, 1500 Mavic 3 Fly More Combo quadcopters were purchased for donations. It cost over UAH 105 million. The device is used by the military for reconnaissance. According to Hotline.ua, the average cost of such a quadcopter on the date of purchase was 106,963 UAH. Come Back Alive bought them for 70,218 UAH per unit. Thus, the foundation saved (106 963–70 218)*1500 = 55, 117, 500 UAH.

Price dynamics for the Mavic 3 Fly More Combo quadcopter during 2022 in UAH

Another example of profitable large-scale procurement: Come Back Alive purchased 664 Motorola R7 VHF NKP portable radios for UAH 28,794 each. And the market price of this product is 29,999 UAH and more.

The INFIRAY (IRAY) Geni GL35R thermal imaging sight costs at least UAH 123,000 on the market, and the fund bought it for UAH 114,000 in October 2022. 90 of these sights are now stockpiled – the organisation's management explains this by the need to have a strategic stock of goods in case philanthropists stop donating in the same amounts as now. "After all, the war will last for who knows how long."

A month before Sergiy Prytula announced the fundraising for the Bayraktar TB2 system for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Come Back Alive purchased this system for the Defence Intelligence of Ukraine. In May 2022, it cost UAH 487 million ($16.6 million against the National Bank exchange rate on the date of purchase).

For most volunteers and charitable organisations, there is no such thing as a salary by default. They work on bare enthusiasm and patriotism, combining volunteering with the main place of work.

Oleksiy Savchenko is responsible for cargo coordination at the Army SOS NGO. According to him, about two dozen people are involved in the work of the NGO now. And none of them receive a fixed salary for volunteering

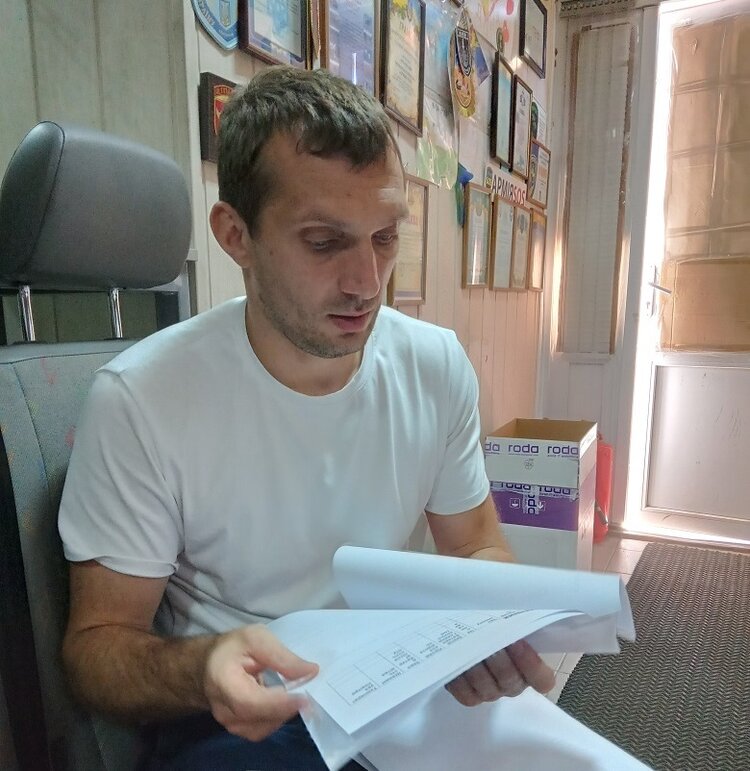

Army SOS volunteer Oleksiy Savchenko

"Some people are paid by the company at their main place of work, and some of them we only help with money – so that some of our volunteers can pay for basic utilities", says Oleksiy during our meeting in the office, which resembles more a garage, "Generally, we have no financial planning. Just like in 2014, we've been landed with a lot of donations now. We raised UAH 70 million during the entire war, and spent over UAH 50 million."

A friendly atmosphere prevails in the organisation's office. People who have known each other since 2014 mostly volunteer here. Local "financier" Hanna Morozova is running through a pile of papers. For more than 20 years she has been in the methodology of business processes in insurance – and she is on first-name terms with accounting either.

"But we have a separate accountant ," she says, "I draw up acts for the property that is provided to us as charitable assistance. And, in fact, we account for all the property that we receive as a gift or buy in Ukraine and abroad."

In Hanna's words, in 99 per cent of cases the organisation provides assistance to military units, and occasionally to individual servicemen: "We provide individual assistance, for example, when a tablet with software installed burned down in the car at the front. Passing one tablet for a military unit through the bureaucracy is very time-consuming, it is more useful to give it to an individual."

Kamikaze volunteers

In addition to charitable foundations and NGOs, so-called solo volunteers are engaged in collecting donations and purchasing everything necessary for the front. Mostly they work through social networks and jungle telegraph.

For example, a well-known volunteer Olena Suyetova works with individual orders from the military and their families. Helping others is her philosophy of life. Working two jobs, she has dedicated a lot of her free time since June 2014 to support the Armed Forces of Ukraine: she collects donations and buys clothes, shoes, generators, radios, medicines, cars and various "goodies", as she calls them, not willing to talk about in public.

The photo on the left shows Ukrainian volunteer Olena Suyetova collecting donations through her Facebook page. Many people who need help find it through social networking sites. The photo on the left shows the opening ceremony of the first monument to volunteers in Ukraine Photo collage by the author

"In the foundations, you sweat away for your salary, and the accountability lies with your manager", says Olena, "I do not want to spend any money not on helping the military, but on my salary. If you are a volunteer who receives a salary, you are an employee, not a volunteer."

Mrs. Suyetova is convinced that, unlike the retarded state apparatus, volunteers are equivalent to the ambulance. Therefore, it is not uncommon for several volunteers to come at the same time to cover the need in one place: "And in the Ministry of Defence it would be like this: 50 pieces of uniform were delivered, 50 registers need to be filled in, then it goes to the warehouse, then they write a request again, because 20 pieces less were brought."

But volunteers have to pay dearly for such efficiency. They often collect funds from benefactors on their own bank cards and have no documentary evidence that they actually bought any goods in favour of them. All a volunteer has is his good reputation.

Charitable foundations try to properly formalise the entire process of supplying aid to the Armed Forces: from the request forms by military units to the taking-over certificates. But it is also a mass phenomenon when the "accounting" exists in the volunteer's Viber: as the correspondence with people who have addressed him with a specific request

Such foundations as Come Back Alive regularly work with foreign manufacturing plants directly, without dealers and intermediaries. As a result, they manage to save money. And solo volunteers or just small organisations do not have such contacts. Therefore, the savings are provided by... purchasing goods without documents – for cash.

Olena Suyetova talks about the backstage of Ukrainian volunteering rather with excitement. She communicates with foreign sellers in English by herself, actively bargains, explaining that the goods will be used for the needs of the Ukrainian army. As a result, in addition to discounts, touched suppliers give "extra" goods as a gift. But this is not always the case.

"When you work like this, you may be ripped off at any time," explains Suetova, "The trouble is that the conditions are set by the seller. This is how I bought sneakers in Poland: I withdrew cash from the card, brought it and handed it over, then I was given the goods. With no documents. And before that I saw those people (sellers – Mind) only via the phone. And there were times when I handed over money in the street, and only later I got shoes. And these were huge amounts. I bought it for cash, because it was much cheaper. And if you do everything properly, officially, then the price is completely different, much higher. I will choose what is cheaper to help more folks."

An "earthquake" at the customs

Volunteers joke that in the first two months of a full-scale russian invasion in 2022, an atomic bomb could be easily smuggled across the border with Ukraine. Some stories about shipping goods for the front line sound like the action movie plots: "At the beginning of the war, a granny brought 62 suitcases filled with Kevlar helmets and body armour from the US to Ukraine. The most interesting thing in this story is that the Americans at the airport simply turned a blind eye when they found out where and why she was carrying it."

Another example: bulletproof vests purchased at the cost of Ukrainian philanthropists were brought to Ukraine hidden between packages of diapers. The paradox of the situation is that now, in the tenth month of the war, volunteers face a great deal of troubles when transporting dual-use goods, not at foreign, but at Ukrainian customs.

When crossing the domestic border, volunteers massively declare goods as humanitarian aid even in cases when they purchased it out of their own pocket. They do this in order to save time (customs officers have fewer questions to humanitarian cargo, and therefore it will cross the border faster) and money (humanitarian aid is exempt from customs duties).

Although in the interpretation of the relevant law, such goods should be a gift from donors for free distribution in Ukraine to be considered humanitarian aid.

The option to declare almost any goods as humanitarian aid simplified the work of volunteers, but at the same time put them at risk of being prosecuted under Article 201-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine: "Plundering of humanitarian aid."

Thus, from the standpoint of law enforcement in Ukraine there are two kinds of volunteers: 1) who work legally and have all the necessary documents; 2) "illegals" who buy goods for cash and usually work almost without papers.

Thanks to the assistance of the Come Back Alive Foundation, the Ukrainian army is equipped with nine out of ten drones, every second Motorola radio, and every third pickup car. Every single sniper of the Armed Forces is equipped with rangefinders, socket adapters, optical sights, weather stations, silencers, rifle stands, photo and video recording systems – because they were donated by the Foundation.

For example, Army SOS arranges delivery of tablets, scanners for radio reconnaissance, components for drones from abroad. Along with the cargo always goes the end user certificate – it is formed by the military unit, certified by the military attaché of the exporting country. For customs, the certificate is a confirmation that these goods will not be sold, but be delivered to the military unit.

And this is an ideal scenario to have no problems with Ukrainian law enforcement.

In practice, for many months of war, volunteers have invented many ways to ship military goods without permits. Yet it is faster and cheaper. Olena Suyetova says that a large number of Polish border guards turn a blind eye to this, "they do not even examine the documents if they see that it is a volunteer foundation. And Ukrainian ones, on the contrary, often shake them down."

This is where customs officers face a moral dilemma: should they prosecute "illegals" who have a noble goal to help the Ukrainian army during the war? Some officers believe that it is worth doing. And they do it for corrupt purposes.

Volunteers bitterly tell about how they bought a batch of radios for the military on the front line at a very favourable price for the money of donors. But all the goods were seized by customs officers because they were transported without documents.

"We bought radios, it was the sixth or seventh delivery... And customs detained them because there was no certification and documents", recalls volunteer Aliona (the name changed due to the risk of criminal prosecution – Mind). "It was just that the military unit could not officially register them. It was a problem, because people donated money to buy radios. We tried to find a way out through our friends, but it didn't work. They never gave them back to us."

Problems also arise for foundations that have impeccable documentation. Oleksiy from Army SOS tells one example of extortion at customs: "Our customs stopped a car with Ukrainian plates, which was carrying 22 pallets of milk powder, 250 bulletproof vests and 500 helmets from Norway. The customs officer decided that he needed "something more". And asked: What can they share with him?"

Or another example. The head of the organisation received a call from customs in the middle of the night – they said that the customs declaration signed by the embassy abroad was missing. "We were asked if we were indeed waiting for the humanitarian cargo? We confirmed. But it was a purely commercial supply, because we bought them and had a certificate with the seal of a military unit and a military attaché. It was a stupid initiative of the customs officer", recalls the Army SOS

The office of the Army SOS NGO. In the foreground is volunteer Hanna Moroz, who serves as a financier.

Volunteers of the Army SOS say that recently they received a call from the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine and were promised to assist in the fight against dishonest customs officials. Saying that "if there is pressure from officials or problems at the border, then call us: we have a team to catch all such evils."

But so far, there have been no public reports of such detentions. But with the help of the Security Service of Ukraine and the National Police, volunteers themselves are more often facing problems with the law due to incorrect paperwork.

"We will find everything – just tell us what"

The 30th Brigade has been at the forefront from the very first days. The Armed Forces have provided uniforms, bulletproof vests, helmets and equipment. But, for example, they had to buy tactical goggles on their own. And since they did not have time to buy them, volunteers came to the rescue

"I do not know who sends us the help. Volunteers cannot contact us directly. They contact the leadership. Commanders make a request, asking us what is needed", says Oleksandr, a soldier from the 30th Brigade, "For example, we ordered quadcopters for infantry reconnaissance, one for each platoon. The Armed Forces do not provide quadcopters. That is, they are at the base, but not as many as needed. Because it is a huge amount of money. Our command has filled out an application. And volunteers write back: We can bring this right now, but we need to raise funds for other pieces, and only then can we complete the order."

There is also active communication between the volunteers themselves. Because often they are approached with requests that a particular person or organisation can not execute – but they can advise where it is better to ask instead.

"We have been on the volunteer market for years, we all know each other. Medicine, for instance, is not our principal assistance, there are foundations that deal with this profile. We switch our appeals to them", explains Andriy Rymaruk, "We also receive orders for drones, because we even have instructors who train our fighters. Without training, a 250,000 UAH drone with a thermal imager is going to be lost: it will fall into the enemy’s territory – and a quarter of million is f***ed up. And this money is hard to find, it is difficult to persuade people to contribute to such purchases."

In order to collect as many donations as possible, volunteers try to be public to the maximum. They shoot videos on YouTube, write posts on Facebook, Twitter, communicate with the media in order to come into the media spotlight as often as possible and thus attract attention. In doing so, they usually behave intuitively, because they do not have communicators in their staff who can professionally interact with the audience.

For example, even the well-publicised Army SOS foundation does not have a media specialist, saying, "we do not work very much in the media, because we do not want to show everything, it is not very safe to attract too much attention." Posts on the official page of the organisation in Facebook are written by volunteers themselves, on a rotational basis.

Posts for the Army SOS crowdfunding company are written by the employees in turns

"Each of our volunteers write posts," says Hanna Morozova, an Army SOS volunteer, "There is a schedule: once in two weeks we have to write one post on the foundation's page. I write the text myself and blur the photo, if people are against their faces being exposed to the public. There are times when we repost something because we were tagged in the publication."

Volunteers often look for the right contacts in Facebook – this is how jungle telegraph works: users advise only their friends and trusted people

Olena Suyetova, even while in Poland, continues to actively volunteer for the needs of the Ukrainian army. She has 21,000 followers on Facebook, and over the years of volunteering, many people have learned about her.

"I have a lot of contacts that can help answer someone's request. I get requests to buy something from many military and volunteers who read me on Facebook", says Olena, "For example, there is a person in a military unit who is responsible for material support. He looks for volunteers to help with the procurement. Then they write a letter that they will receive these products for the military, not for sale."

Yuliya Pavlenko, International Operations Director at Ukrposhta (Ukrainian Post), has been delivering humanitarian aid to Ukraine from Western Europe on a volunteer basis since the first days of the war. According to her, this war has shown that there are no barriers in communication between people, if they are united by a common goal.

Yuliya Pavlenko, International Operations Director at Ukrposhta, shows chats with top managers and government officials of Ukraine, the United States and Europe on her phone. She never turns off her smartphone, day or night, because at any moment she may receive a call from overseas to discuss humanitarian aid to Ukraine

"During the first few weeks of the war, I always picked up the phone from unknown numbers and always called back, because I knew that it could be someone very high-profile," says Yuliya Pavlenko, "Many people ignored their positions and statuses. Everyone communicated on equal terms. And at some point you find yourself in a WatsApp chat together with the owners of large corporations – Fozzy Group, Rozetka – and begin to think about how best to deliver humanitarian aid. It was an incredible number of acquaintances. That is, a minister could call me and say: John Doe gave me your phone number. And that's it – we start talking to the essence of the issue. And everyone helped everyone."

Often the military do not even know the names of volunteers and NGOs that helped them to get everything they need. Soldiers turn to their commanding officer with a request for what they need. And he then assigns the task to the person responsible for the logistic support of the unit.

Oleg Dombrovsky, the Acting Head of Moral and Psychological Support at the Territorial Defense Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine served almost the entire war in the Mykolaiv direction. With 20 years of officer carreer, he states that in recent months the organisation of communication between volunteers and the Armed Forces has improved significantly.

The officer says he has only positive impressions of cooperation with volunteers. Like, "if there were no volunteers in Mykolaiv province, we would have survived, but at a greater cost."

"If people know you, they come to you and offer help", says Oleg Dombrovsky, "I talked to four volunteers about supporting my unit. Everything was very well organised. There was no miscommunication between the military, civilians and local authorities. Senkevych (Oleksandr Senkevych, Mykolaiv Mayor – Mind) and Kim (Vitaliy Kim – Head of Mykolaiv Oblast State Administration – Mind) were active: they communicated with district administrations, businesses. Where to get concrete, human resources (specialists). This helped to contain the russian offensive on Odesa."

Fact-checking for the sake of life

Volunteers carefully check each application for assistance. Because equipment is a constant shortage during the war. So the priority is always given to the military who need it here and now, because they are carrying out a combat mission.

"For example, it is difficult to understand whether someone needs a bulletproof vest", explains Oleksiy from Army SOS, "The military can simply ask for a spare bulletproof vest. Or a person is sitting in the deep rear, but asks for armour because it is safer for him or her. We help only those who are on the forefront."

A voice on the phone that says it is a military man calling is thoroughly checked. Volunteers ask for supporting documents and look for mutual acquaintances to make sure that such a person with such documents really exists.

"Our volunteers pester the applicants: sign an act from the military unit, give your documents, military ID, which indicates in which unit the person is at the moment," Army SOS describes the daily routine of fact-checking.

Andriy Rymaruk says that the Come Back Alive Foundation has a whole department that deals with verification of online applications with the needs of the military unit. There in a special form you need to specify the name of the unit commander, his position and rank, contact information. The need itself, brigade number, element name, military unit number and its subordination should be described.

"A company commander says, for example, he needs four thermal imagers and five UAVs. And this is too much for the company, one or two thermal imagers will be okay," says Rymaruk. "The manager contacts the commander and asks if the company really needs it. And the commander clarifies how many are really necessary, because someone else from the volunteers has already brought it."

Further, Come Back Alive contacts other foundations to make sure that the same need is not covered by another foundation or the state.

"We have established communication from the battalion commander up to the Commander-in-Chief", the Foundation explains, "We can also refuse to supply thermal cameras, because when one asks for so many thermal cameras and I have information on how many he received from the state, how many other volunteers gave, I understand how many he really lacks. And such situations happen on a daily basis".

Come back alive puts the serial number of the product with the "Sale Prohibited" disclaimer on each tablet for the army

Hanna Morozova from Army SOS says that together with experience come knowledge and understanding of how to properly check the accuracy of the request from the military. And it is not only about overstated, but also about understated requests – when military units ask for even fewer items than they really need. Just to have "at least something."

"People leave information in our GoogleDoc about what they need about the request, who needs aid, who is the signatory," says Morozova, "And we check whether it is a real request, whether it is overstated or understated. Because they can write that they need six tablets, but in fact they need as many as 16. Because we know that a team of military engineers needs a certain number of tablets. When they do demining or mining, this info is entered into the programme using the coordinates. When they say it is such-and-such artillery, we know how many tablets are needed per battery or unit."

Olena Suyetova explains that it is easy for her to verify the authenticity of the applicant's words as well, because for many years she has already acquired a lot of working contacts in the military sector: "Yesterday a volunteer calls and says that such-and-such battalion needs 150 tourniquets. Once I helped him. I find out that everything is okay in this battalion. They give me the contacts of their chief medical officer, and he says that 50 new people have joined and if you give them 50 CATs, it will be great. I call the volunteer back and say that I need not 150, but 50 tourniquets. He says: 'This is my neighbour, he could not lie to me'. But neighbours can also be different, and there's always the corruption component. It all just needs to be checked."

Photo reports on the delivered aid for the military display that the organisation can be trusted

Oleg Dombrovsky served in Mykolaiv and was engaged in the repair of military equipment. He worked directly with local volunteers because he knew them well.

"The bulk of the vehicles are brought by volunteers", he says "Now the mechanisms of volunteering are well defined. The materiel is transparently delivered to the unit. The risks that it would end up in the wrong hands are minimised. We receive a request from a unit. All applications come to a single centre, are processed, verified, and it becomes clear that these are not fraudsters."

Each product that is delivered as humanitarian aid must be registered. But without such reporting, volunteer organisations can be inspected at any time and brought to administrative or criminal accountability

Volunteer Maryana Dvulit is also the supervisor of the Women Health Centre at JSC Ukrzaliznytsia (Ukrainian Railroads). She used to organise the collection and delivery of humanitarian aid to the de-occupied areas and for internally displaced persons. Her phone is bursting with messages and calls.

"When someone called and asked us for help, we checked, for example, the residence registration, the IDP certificate", the woman says.

At the same time, both the volunteer and her team try to work as transparently as possible. So that everyone could see that the donated medicines, food, clothes reach the recipients. She shows numerous photos and video reports that she publishes on social media.

"Our volunteers travelled to Melitopol along unmapped paths to bring aid to civilians", says Dvulit, "Together with the team we checked and called people to see if everything had arrived, if everything was okay. But fortunately, we are surrounded by decent people. And this gave us confidence. If there is someone who deceives us, our military and volunteers will quickly deal with them."