Payment for the Land. How conflict between local communities and a multinational corporation is escalating in Colombia’s major coal-producing region

Why some of the poorest people in the country live next to Latin America’s largest coal mine

The project is implemented with the support of the Bertha Foundation.

By Liubov Velychko

La Guajira is Colombia’s northern region, a semi-arid peninsula on the Caribbean coast, home to Indigenous peoples, including the Wayuu. It is one of the country’s poorest departments, despite holding Colombia’s largest coal reserves.

La Guajira is home to the massive Cerrejón open-pit coal complex, which for decades has shaped the local economy and profoundly affected the environment. Coal mining has become a key driver of conflict between the state, transnational corporations, and local communities that have lost their land, water, and traditional way of life as a result.

As part of the Bertha Challenge project, implemented with the support of the Bertha Foundation (an international non-profit organization promoting social and economic justice), Mind publishes a report by special correspondent Liubov Velychko on the confrontation between local communities and a coal company in the region.

Two Sides of the Conflict

Less than five minutes after I began photographing the railway tracks used to transport coal for export to Europe, a cyclist in a black uniform and mask rushed up to me. He did not introduce himself, but in a stern tone said he worked for the railway security service and demanded that I leave the area immediately. He explained that terrorist attacks allegedly occur here frequently and that he was responsible for ensuring security. The stranger also forbade me from taking photographs, claiming the site was private property.

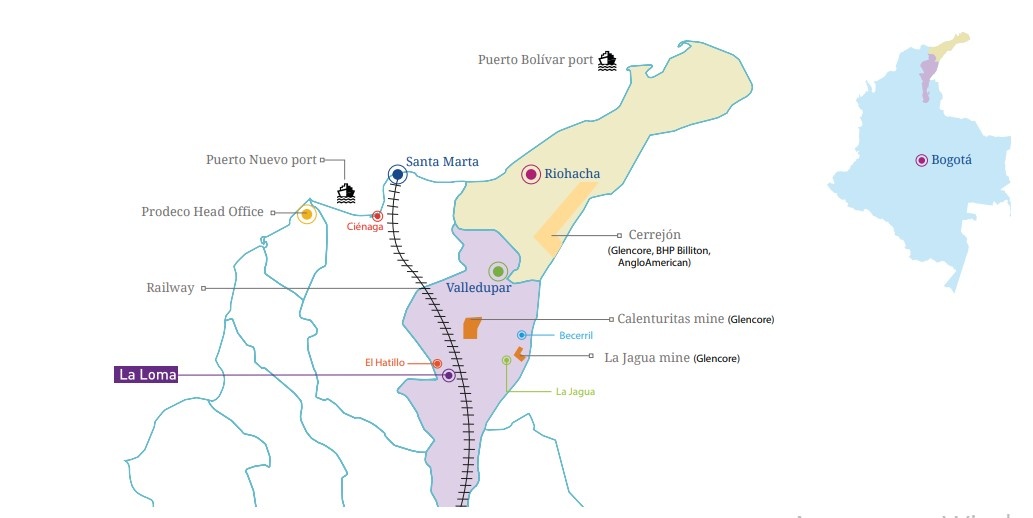

The owner of the railway is Glencore. It is one of the world’s largest commodity and natural resources companies, registered in Switzerland, and engaged, among other activities, in the extraction and trade of raw materials. Glencore controls one of the largest coal mines in the world — El Cerrejón in northern Colombia, from where this report is filed.

Ironically, the region where millions of tonnes of coal are extracted each year by a workforce of around 11,000 is one of the poorest and least developed areas in Colombia. Local residents say this glaring injustice is the result of collusion between a corrupt government and the interests of a private company. A significant share of the coal from the region is exported to Europe. The company pays taxes into the state budget, which, according to local activists, explains the Colombian government’s consistent support for Glencore.

All of this is accompanied by a large-scale information campaign in Colombia’s major cities, aimed at portraying the problem as non-existent and shaping a positive image of Glencore in the La Guajira region. In leading media outlets, the company is presented as a responsible investor that protects the environment and cares for local communities.

In response, local activists have created their own information channels on social media and a website. However, they believe these steps are insufficient to effectively convey their position to a wider public — one that fundamentally contradicts the narrative promoted by Glencore.

As a result, people protest not only online but also offline.

The owners of the coal company seek to control the area around the railway tracks, as local communities regularly stage strikes there and block coal wagons. People are outraged because polluted water from the coal mines flows back into the river used by local residents. Yet, according to the activists interviewed for this report, neither the company nor the government has responded to these concerns.

In its reports, Glencore and its subsidiary Prodeco present an extensive system of self-regulation: membership in the “Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights” initiative, regular training for management, employees, and even private and state security personnel.

The company claims cooperation with the UN, long-term biodiversity conservation policies, wildlife rescue programs, land reclamation, reforestation, and water resource management initiatives.

According to Prodeco, all of this is accompanied by “continuous monitoring” and corrective actions, as well as formal oversight by the Colombian environmental regulator. At the same time, the company independently collects data on the environmental impact of its operations and submits it to authorities — without, activists say, independent or publicly verified validation.

Scientific studies initiated by local communities indicate that the water is contaminated with chemicals and now contains high levels of carcinogens, potentially triggering cancer. Consequently, drinking water from local wells is unsafe.

Families spend a third of their household budget on water delivered monthly by truck. Those who could not afford to buy water and relied on the polluted local supply have begun developing cancer. This situation has persisted for 13 years.

Meanwhile, the National Agency responsible for environmental standards maintains that everything is fine and that there is no negative environmental impact.

Background:

Colombia is one of the world’s leading coal exporters, producing over 60 million tonnes in 2023, rebounding after a pandemic-related decline. More than 90% of this coal is extracted through open-pit mining in the northern departments of La Guajira and Cesar, with almost the entire output destined for export.

El Cerrejón, the largest coal mine in Latin America, produced about 19 million tonnes in 2024. Its owner, Glencore, plans to reduce production to 11–16 million tonnes per year due to low prices and logistical costs.

Colombian coal is traditionally exported to Europe (notably the Netherlands and Germany), North America, and Asia. An increasing share of shipments goes to Asia-Pacific countries, though annual export volumes vary by year and market.

The department of La Guajira, home to Cerrejón, is heavily dependent on mining: coal accounts for a significant portion of the local GDP (estimates up to ~40% or more), and a large share of regional revenue comes from royalties and taxes paid by the mine.

Glencore gradually consolidated control over Cerrejón: in 2021–2022, it bought out BHP and Anglo American’s shares for approximately $588 million, becoming nearly 100% owner.

Several thousand people work at the mine — estimates range from 9,000 to 12,000, mostly men. Cerrejón has traditionally generated substantial export revenues (over $2 billion per year at peak periods), but current market conditions and political decisions, including export restrictions to certain countries, complicate its prospects.

Overall, Cerrejón’s production, exports, and ownership constitute a key part of Colombia’s coal sector and La Guajira’s economy, while the region remains highly exposed to external markets, global prices, and regulatory risks.

Out without belongings

82-year-old Francisco Espinay spent his life raising livestock — until armed police forced his family out of their home under threat of death. This was in 1999, when the company reached an agreement with the government to begin coal mining in this resource-rich region.

To start extraction and build the necessary logistics (including railway lines for transporting coal), the company needed to clear settlements from the land. According to local residents, law enforcement used force against those who refused to leave.

The state justified the evictions by claiming that coal must “serve the nation.” Since 2016, with police involvement, at least 20 communities have been forcibly removed from mining areas. On average, each community had about 300 residents. Activists report that people were displaced without alternative housing — essentially thrown onto the streets.

39-year-old Claire Carrillo recalls how, as a child, her family was forced to sell a spacious home, a two-hectare orchard, and a farm with ten pigs, hundreds of chickens, and two cows for next to nothing.

“Glencore blocked all access roads to the village so teachers couldn’t get to school,” Claire says. “I missed a year of education. Then the company cut off our electricity. Later, they threatened that if we didn’t sell the house, they would simply demolish it.”

During the demolition of houses with bulldozers, some residents stayed inside, trying to stop the destruction. Police forcibly removed villagers from their homes.

In 2002, Claire’s mother accepted compensation from the company for the lost land — five thousand dollars. This amount was disproportionate to what was lost. With this money, the family bought a small, old house in the nearby town of Antonuevo. But it was a forced choice: either leave without compensation or receive at least something.

Legal Battle

This is how farmers lost their livelihoods and became trapped in the city. Like many other victims, Claire is preparing a lawsuit seeking full compensation for her lost house, orchard, and livestock. However, this process is expected to be long and complex.

Back in 2012, residents filed a legal claim demanding new land plots, housing, and conditions to rebuild their community. The court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs: the municipality was required to provide land and funding for the construction of new homes.

Despite the court decision, neither the local authorities nor the company fully implemented it.

Western media reports and press releases rarely mention these events or Glencore’s role in forcibly displacing communities. This context is systematically absent from the international media narrative.

In 2001, the coal-mining area was home to about 400 Wayuu Indigenous families. However, Glencore commissioned an expert report (available to the author) claiming that the residents did not belong to Indigenous or ethnic farming communities. This document was presented to the municipal authorities as justification that the company’s activities did not violate Indigenous rights, and the authorities ignored the misinformation.

In its official reports, Prodeco portrays the relocation of communities as an exemplary process allegedly compliant with International Finance Corporation, World Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank standards. The company claims a “fully participatory approach” and emphasizes that its main goal is to preserve community livelihoods, stating that relocations are conducted “according to the wishes of the community itself.”

Corruption Trail

30-year-old community leader Gabriel Almaso lived in a camp for internally displaced persons from age seven to twenty-four — homes made from cactus. This followed his grandmother being forced to sign over land to the company. According to him, she was threatened that if she refused, bulldozers would destroy the houses along with the people inside.

Today, Gabriel is fighting to defend his rights against Glencore and its subsidiary Prodeco. He says his ancestors, the Wayuu Indigenous people, have lived in the area for at least 500 years. His family once kept goats, horses, and donkeys, including mules — hybrids of horses and donkeys — that were essential to their livelihood. Stores were unnecessary, as they grew their own food. Now, the community has almost no access even to drinking water.

Gabriel recalls that in 2002 the company decided to further expand coal mining and held consultations only with the then-community leader. According to community members, the former leader misled people: she presented documents as if they were for receiving food aid. In reality, the papers were consent forms transferring land to the coal company. Most residents were illiterate and signed with a fingerprint, believing it was a mere formality.

As a result, an agreement was signed transferring roughly 1,000 hectares of land under Glencore’s control. On this land, a railway was later built — a key infrastructure for transporting coal from the mine to the ports.

Activists claim that this woman received a bribe from the company, equivalent to about $18,000.

But that was long ago; the former community leader has since passed away. Residents say Glencore is now trying to involve her son to validate the legitimacy of the agreement. The company relies on those fingerprints as evidence that the community voluntarily agreed to transfer the land.

Based on this, the company insists on the legality of its actions in court cases regarding compensation for roughly 1,000 hectares of land. Gabriel’s family had cultivated vegetables and watermelons on this land for generations. The total compensation the community is claiming amounts to approximately $235,000.

According to activists, the company offers food aid (including rice) to negotiate with residents. Gabriel’s community firmly refuses these supplies as a form of protest.

“The Prodeco director repeatedly offered me a bribe,” Gabriel says. “$131,000 in exchange for dropping the lawsuit. The calls come every two months, but I refuse each time.”

Instead, he demands a systemic solution, including the construction of a plant to convert plastic into fuel.

“My happiness will be when we can return our ancestors to their land, when the version of history the company tells against us is disproven, and when we win in court,” Gabriel adds.

I contacted Glencore through their corporate website requesting information on how many Indigenous residents have received compensation and the total amounts paid since the relocations. At the time of publication, the company had not responded.

Attempts to Return Home

Local environmental activists say Glencore is already considering leaving the region earlier than the originally planned 2035 timeline. They fear the company may depart without restoring damaged land or addressing the consequences of decades of coal extraction, leaving reconstruction to the communities themselves.

On their own initiative, a few brave individuals are beginning to return to the land where their homes once stood. 67-year-old Thomas Vstate is one of them. Ironically, coal mining never began on the site of his former village. Legally, the land no longer belongs to him — it was taken by the coal company — but he remains undeterred, seeing it as his homeland.

Thomas’s house was demolished in 2016. He says he was not allowed to take a single possession; the bulldozer flattened everything he owned. He also lost his livestock: a flock of 500 sheep, pigs, and cows. When the bulldozer approached the house, Thomas tried to convince company representatives not to destroy his property.

For his demolished house, Thomas received compensation — less than $10,000. This amount was insufficient to buy a new home with land for farming. Living in the city was not an option for him.

“I cannot live in the city — without animals, without a garden,” he says. He also refused to live in the so-called “new village”: the houses were poorly built, with leaking roofs and holes in the walls. Most importantly, there was no land for farming.

With only the foundation of his old home remaining, Thomas constructed a new house from available materials: wooden poles, sheets of metal, tarpaulins, and corrugated panels. Community activists supported him in resisting pressure from the company, which opposed his return. About a year ago, Glencore ceased attempts to evict him, and since then Thomas has remained undisturbed.

Thomas’s main wealth now lies in his livestock: pigs, about 20 cows, goats, and chickens. Parrots and puppies also live in his yard. Some of the animals he purchased, while others were gifts from friends.

Today, Thomas says he is happy. But this happiness came at the cost of many years of struggle. The state remains silent, and people are left to rebuild their lives from the fragments — alone, on the land that was once their homeland.