Next one down: Why did the US First Republic Bank experience a collapse?

Who will benefit or lose from the urgent buyout of the bank's assets?

At the beginning of this week, news emerged about the redemption of assets of another bankrupt bank in the United States – First Republic Bank (FRB). This news almost coincided with the meeting of the US Federal Reserve System, which took place on Wednesday, May 3.

And earlier, in late April, another important event occurred – the publication of a report by the Federal Reserve System on the collapse of FRB's 'predecessor' – Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). This phenomenon is exceptional – the Federal Reserve System had not previously disclosed such materials, intended mainly for internal use.

Mind continues to analyse the problems of large Western banks and their origins. Therefore, we offer a detailed overview of events surrounding the First Republic Bank, and in the future – a continuation of the topic with an analysis of the details of the April report by the Federal Reserve System.

Read also: Why Credit Suisse "nearly" went bankrupt and whether it has a chance to survive

What happened to First Republic Bank, and why is it important?

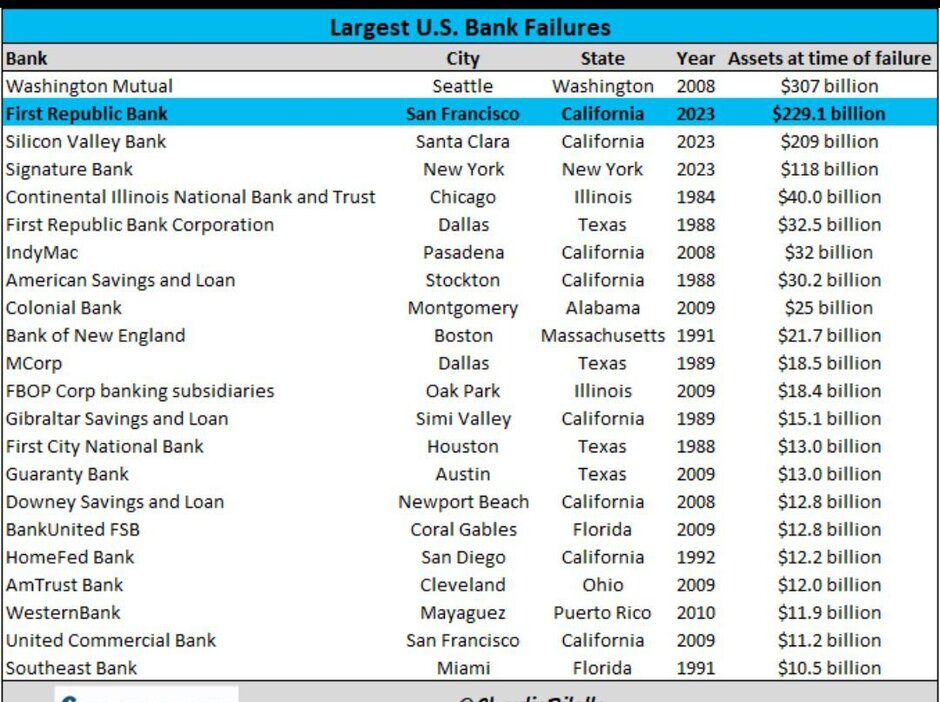

After its collapse, First Republic Bank moved from second to first place in the table of the largest banking bankruptcies, surpassing SVB. If we add Signature Bank to this pair, we get interesting results: three out of the four largest bank bankruptcies in the last 40 years happened in 2023.

Source: FDIC

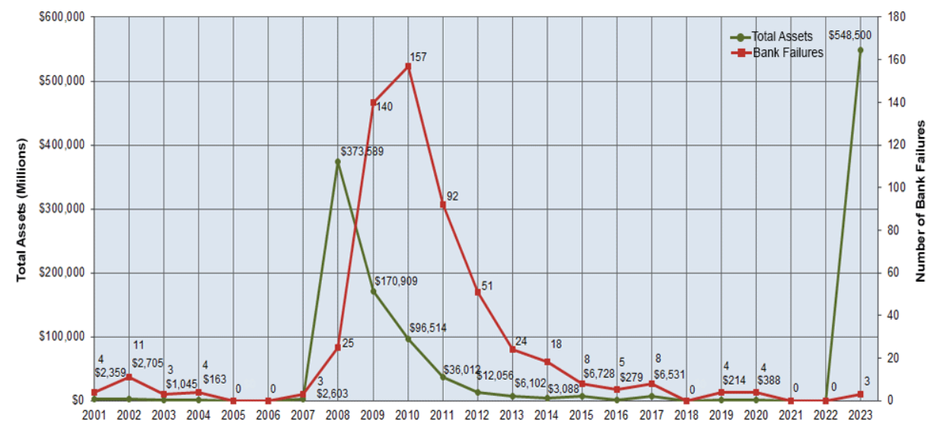

The situation is even more striking on the graph, where there has been complete calm in recent years.

Source: federalreserve.gov

The right scale shows the total number of bankrupt American banks per year (red line), while the left shows their assets (green line). The balances of the three aforementioned banks reached nearly $550 billion, surpassing the result of the memorable 2008 ($374 billion).

However, for fairness, it should be noted that at that time, investment banks took the brunt of the blow: Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers had a combined asset base of more than $1 trillion. Now we are talking about classic banking institutions.

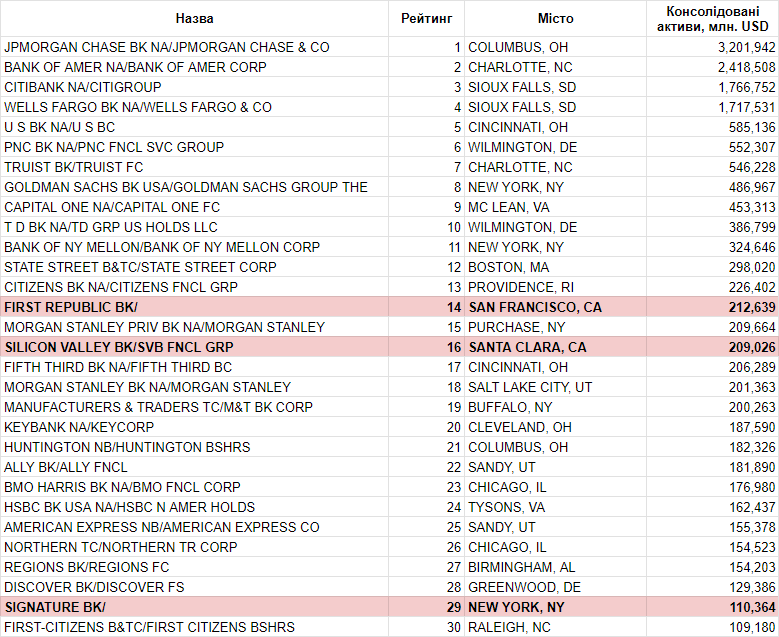

To understand the scale of events, it is important to look at the numbers in context. The assets of the US banking system as of mid-April amounted to $22.9 trillion. Therefore, First Republic Bank accounted for 1% of the system, and together with SVB and Signature – already 2.4%, which is a significant share.

At the beginning of the year, all the aforementioned banks were in the top thirty largest.

Now, more details about FRB. The problems began unexpectedly. Throughout last year, despite the rise in interest rates, the market reacted calmly – the bank's share price was declining, but there were no panic moods.

The trigger was the situation around SVB in early March. At that time, investors and analysts suddenly became alarmed and began playing the "Find the next problem bank" game.

Why did it happen right now?

Lists of 'risky' banks were published on popular information resources, and the topic was actively spread on social media. In our review, we have written that the financial position of FRB looks stronger and have even provided a comparative chart with the dynamics of deposits.

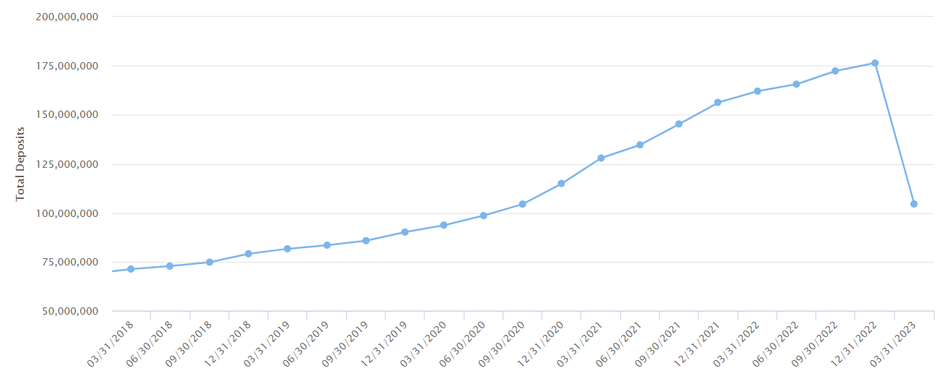

However, that's the nature of dynamic indicators: what looked stable yesterday could easily change. On April 24, First Republic Bank published the results for the first quarter of the year (Form K-8), which confirmed the most pessimistic expectations.

As stated in the report itself, as of March 9, the bank had $173.5 billion in deposits, only 1.7% lower than at the beginning of the year – meaning there were no problems and the bank was operating normally.

However, following the events surrounding SVB, depositors began to withdraw their deposits. It was then possible to arrange a stabilisation loan of $30 billion from a group of banks as a rescue circle. Later, FRB turned to other sources of resources.

But the final situation became clear from the quarterly report:

By the end of the quarter, deposits had fallen to $104 billion, a 40% decrease compared to the beginning of March. Moreover, this amount includes $30 billion in assistance from banks. If we exclude it, the remaining 'market' deposits amount to only $74 billion – losses have reached $100 billion.

The classification of deposits into insured and uninsured explains the situation:

FRD deposits, $ million

| 31 December 2022 | 31 March 2022 | |

|

Total deposits |

176,437 | 104,474 |

| Without banks' assistance | 176,437 | 74,413 |

| including insured | 57,615 | 54,648 |

| including uninsured | 118,822 | 19,765 |

The bank's liability structure was dominated by such large deposits, for which depositors could not rely on insurance, which helped to shake the situation (67% of deposits belonged to this category at the end of the year).

Mind's note:

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) began operating in 1934. Since then, as proudly noted on the organisation's official website, "no depositor has lost a single cent of insured funds."

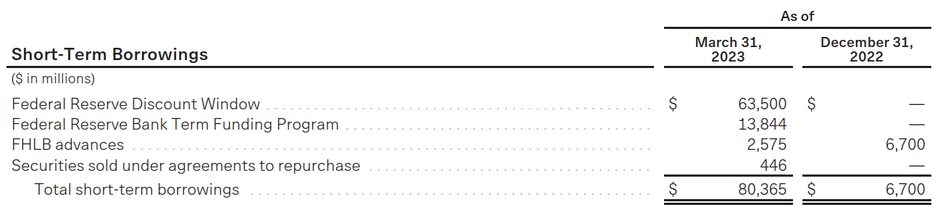

In fact, starting in March, deposits were being replaced with short- and long-term loans. The bank became a client of the Federal Reserve's Discount Window, the lender of last resort. When the Federal Reserve Board sets target rates, it refers to rates in the interbank market, where banks typically lend to each other, ensuring system stability.

However, turning to the Fed (discount window) for loans directly is often an indication of a bank's problems and the unwillingness of the market to lend to it. The Fed sets these rates not as target benchmarks, but strictly. At the same time, the regulator seeks banks to resolve most of their problems among themselves, without resorting to the discount window.

However, at the end of the quarter, the bank's short-term loans reached $80 billion:

Is the bank solely responsible for everything that happened?

Objective difficulties the bank faced do not exclude its own mistakes. The bank eagerly accepted deposits from clients and used them to expand lending, primarily mortgage lending, which is long-term by nature. So, by the end of the year, the bank had a portfolio of residential mortgages worth $121 billion. By the end of the first quarter, the amount of these loans had even increased slightly, despite the run on the bank. It is clear that in case of an outflow of depositors, quickly getting rid of mortgage loans and settling all obligations is not possible. This is especially evident when looking at the structure of deposits.

Take the end-of-year data again to understand the picture that preceded the bankruptcy. The interests did not accrue on the current accounts worth $67 billion. And for deposits that did earn interest for clients (a total of $104 billion), the average rate was 1.63%.

How much faith do clients need to have in a bank to continue keeping their money there with such rates, when alarming warnings are everywhere? The bank faced a choice – to drastically raise rates, which would instantly be reflected in financial results, or to make only minor adjustments, hoping to avoid a 'run' by depositors.

As the Fed emphasises in its report, "the combination of social media, a concentrated depositor base, and technology may have fundamentally changed the speed of runs on banks. Social networks have allowed depositors to rapidly spread concerns, and technology has allowed for the instant withdrawal of funds."

Thus, the external stability and profitability of a bank can often have a reverse side – saving on resource mobilisation and an unstable client base, as a result. The question is whether clients would have continued to keep their money steadily, even with higher rates than market rates (reading articles such as this one that directly indicate the risks of their bank). And to what extent can the payment of interest on current deposits, which can be withdrawn at any time, be systematically justified?

Looking back, it's easy to say that the bank shouldn't have expanded its mortgage portfolio with such enthusiasm and left the money from current accounts effectively uninvested. However, these judgments are at odds with the general practice of banking, where current deposits, circulating between banks, create a multiplier effect of money growth in circulation.

Why were First Republic Bank's assets decided to be sold?

Recognizing the lack of prospects for the bank's recovery under the circumstances, a competition was announced for the purchase of its obligations and assets. The latter have a market nature and can generate profits.

The issue was not related to low-quality investments or loans (as we observed with Credit Suisse), the bank ended the quarter and last year without losses. The profit for the first quarter was a decent $269 million. For comparison, the first quarter of 2022 brought $401 million, and the fourth quarter of 2022 brought $386 million, respectively.

Of course, possible hidden losses that will be realised later should not be ruled out. As practice shows, banking reporting may contain a significant creative element in addition to dry calculations.

The largest American bank, JPMorgan Chase & Co., with assets of over $3 trillion, won the competition. The buyer will pay $10.6 billion to FDIC immediately and commits to adding another $50 billion over five years (which allows covering about $60 billion of insured deposits at the time of the bank's collapse).

Who wins, and who loses in this scenario?

The deal looks attractive for everyone except for FRB shareholders: the bank's securities have practically fallen to zero. JPMorgan will take over a package of loans worth more than $175 billion and other assets.

As for interest rates, despite reports in the media of "30-year loans at 1%," these are likely isolated cases. The bank's real loan portfolio before the crash had higher yields (3.18% for residential mortgages and 4.15% for commercial).

Of course, in case the economy enters a recession, these portfolios may lose quality, as property prices and borrower solvency will fall under such conditions. Moreover, the current yields are not even close to the rate of the Federal Reserve and the discount window rate at which First Republic Bank has been forced to obtain resources.

Overall, it appears that after several high-profile bank failures, American regulators, along with the country's leading bankers, have shown an optimal scenario for resolving such problems. Namely, to allocate assets that have value and find a market buyer for them. The interests of problem bank shareholders are not considered at all, and the burden on the FDIC is reduced by the asset buyer.

How exactly was the buyout organised?

An SLA (Shared Loss Agreement) was reached between the FDIC and JPMorgan Chase. The mechanism itself is not new, and on the FDIC website, there are answers to key questions about it. In particular, emphasis is placed on the fact that taxpayer money is not involved in the rescue of problem banks under this scheme.

It would have been preferable, of course, to do this before a full-scale run on the bank, but then the buyer is unlikely to be able to claim a significant discount on asset prices. However, to understand why everything happened the way it did, it is worth considering the role of large banks and looking at the situation through the regulator's eyes. The FRB story, in our opinion, is not an issue of a single bank and is closely related to two other bankruptcies.

So let's sum up. The bankruptcy of FRB became the next, and already, one might say, an inevitable result of changes in economic conditions. Conditions that are seriously detached from real economic realities – when the regulator and market participants are forced to quickly 'do a flip-flop' between soft periods of excess liquidity and subsequent stages of tough policies.

Banking problems become a convenient reason for the Fed to increase its role. At first glance, a self-critical report on the situation with SVB can be a step towards changing legislation and regulatory requirements. As for purely market mechanisms of regulation, their role may decrease – attracting an investor to the capital of a problem bank becomes a thankless task, as such investors risk the most.

What exactly was in the Fed's report, and what this document shows in terms of studying the risks of the activities of large banks, Mind explains in detail in the next article.

If you have read this article to the end, we hope that means it was useful for you.

We work to ensure that our journalistic and analytical work is of high quality, and we strive to perform it as competently as possible. This also requires financial independence. Support us for only UAH 196 per month.

Become a Mind subscriber for just USD 5 per month and support the development of independent business journalism!

You can unsubscribe at any time in your LIQPAY account or by sending us an email: [email protected]